Our Blog

Theory and Practice

added: 05.01.2014, by Mike Spinney

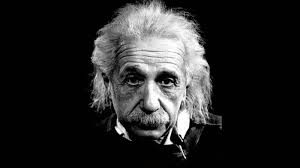

“In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.” – Albert Einstein

Spent yesterday afternoon on the campus of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. That’s not unusual for me since my daughter attends the school (you’ll indulge a proud dad, won’t you?) and I live close enough to visit often. But yesterday I was there to attend an IAPP KnowledgeNet meeting.

Besides affording me the chance to visit Woo Town and drop in on my daughter on a week day (it’s finals time, though, so just briefly), there were some interesting items on the agenda. In particular, two members of the WPI faculty presented on privacy-related projects. Our faculty host, Prof. Craig Wills, has done groundbreaking research on how personal information is leaked to third parties while in the process of engaging web sites and social media (well before this was a major concern for most).

Besides affording me the chance to visit Woo Town and drop in on my daughter on a week day (it’s finals time, though, so just briefly), there were some interesting items on the agenda. In particular, two members of the WPI faculty presented on privacy-related projects. Our faculty host, Prof. Craig Wills, has done groundbreaking research on how personal information is leaked to third parties while in the process of engaging web sites and social media (well before this was a major concern for most).

To open the afternoon, Prof. Craig Shue talked about research conducted on behalf of law enforcement that could help law enforcement agencies geolocate cybercriminals within one hour without having to go through the time consuming (up to a month or more) and notoriously unreliable process of obtaining a warrant and requesting user information from an ISP. Known as the Marco Polo Project, Dr. Shue’s efforts to date seem to show that the process, while itself imperfect, holds a great deal of promise.

Shue described (in simple terms, thankfully for my limited cognitive ability)how, when using a wireless router (as is often the case), a cybercriminal’s IP address can be pinged by packets of varying and unusual sizes and the responding transmissions can then be detected by a patrol car outfitted with a listening device. Through a process of triangulation, it is possible to home in on the offender. Shue said that, having proven the concept, the technology could be adapted for use by drones which could more quickly and efficiently navigate and sniff out their target.

Prof. Wills went last and talked about some of his work in identifying the “longitudinal privacy footprint” of online properties and how—whether disclosed or not—data collection and “leakage” takes place without an individual’s knowledge.

Of course, with a lecture hall filled with privacy pros, there was much consternation. The Marco Polo Project treads on some rather shaky ground. Wills’ use of the term “data leakage” didn’t align with the way some technology companies define it. What if companies had covered their data sharing practices in their privacy policy?

All valid points, I suppose, but they expose a fundamental flaw in the way we approach privacy protection. Regulations and policies are often crafted with what seems like an assumption that, having committed words to paper, all affected parties will take the time to understand and comply with the regulation or make informed decisions. But that assumption does not reflect reality. People are going to do what they want to do and they will take the path of least resistance. If that means using a boilerplate privacy policy that doesn’t come close to reflecting actual practice, or if it means clicking an end-user licensing agreement without actually reading the (multi-page legalese) document, so be it.

Both Shue and Wills seemed bemused at the questions, patiently explaining that their research is focused on understanding what’s possible and on actual behavior.

For me, it was more support for my position that the privacy profession needs to do a much better job at understanding and operating within the boundaries of actual consumer behavior rather than cling to the futile hope that they will pay attention to more rules and warnings and behave the way someone else thinks they should.

Share This Article: